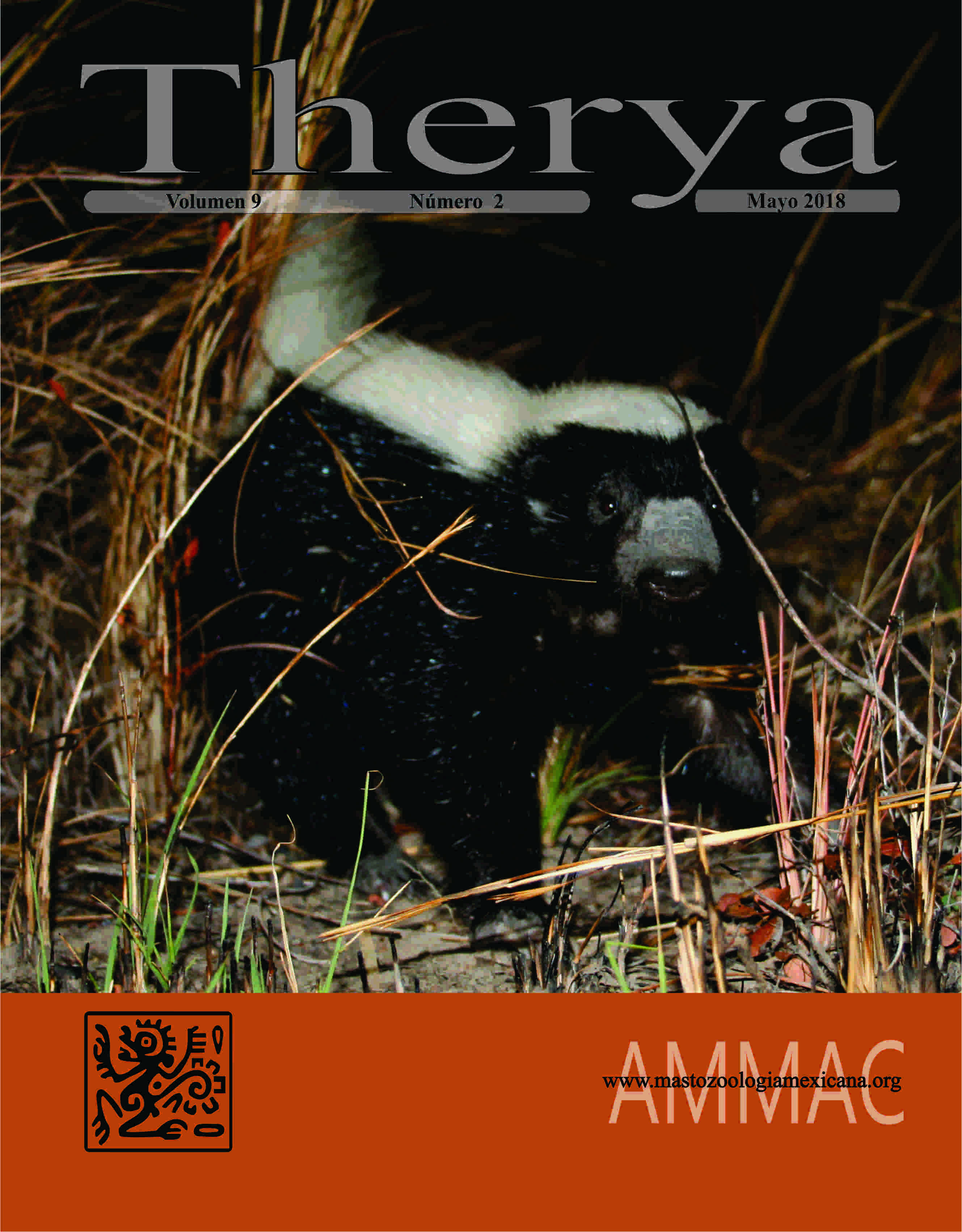

New records and estimation of the potential distribution of the stump-tailed porcupine Coendou rufescens

Keywords:

altitudinal range, distribution model, mammals, protected area, vegetation remnantsAbstract

The stump-tailed porcupine (Coendou rufescens) is a medium-sized species that inhabits subtropical, temperate and High-Andean forests of the northern Andes, at 800 to 3,650 m asl. This species is characterized by a short non-prehensile tail and a distinctive reddish color. Here, we report new localities for Coendou rufescens in Ecuador based on direct field sightings and the revision of mammal collections. In addition, we conducted a review of literature records of C. rufescens throughout its distribution range. A total of 52 georeferenced records were modeled for the potential distribution at the regional level (Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru) based on 19 bioclimatic variables. Finally, we overlaid the layers of vegetation remnants and state protected areas. We report 10 new localities for Coendou rufescens in Ecuador; these records are concentrated to southern Ecuador between 1,120 to 4,387 masl. Fifty two records found that the bioclimatic variables Temperature Seasonality (BIO4) and Minimum Temperature of the Coldest Month (BIO6) associated with the type of habitat made the greatest significant contribution to the distribution model of C. rufescens. The suitable habitat for the species spans across ~ 448,820 km2, with 50.4 % in Colombia. These findings indicate that the locality Camino del Inca in Sangay National Park, at 4,387 m asl, is considered the highest-elevation record for C. rufescens and the family Erethizontidae. Colombia and Peru include the highest proportion of potential habitat across its range (40.2 % and 32.7 %) based on remnant vegetation; however, Ecuador maintains the largest proportion of the porcupine distribution within protected areas (35.5%), with a larger extent of landscape connectivity, essential for the conservation of C. rufescens.References

Aguirre-Gutiérrez., J., L. G. Carvalheiro, C. Polce, E. E. van Loon, N. Raes, M. Reemer, and J. C. Biesmeijer. 2013. Fit-for-purpose: species distribution model performance depends on evaluation criteria–Dutch hoverflies as a case study. PloS One 8:e63708.

Alberico, M., V. Rojas-Díaz, and J. G. Moreno. 1999. Aporte sobre la taxonomía y distribución de los puercoespines (Rodentia: Erethizontidae) en Colombia. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 23:595–612.

Albuja, L., A. Almendáriz, R. Barriga, F. Cáceres, L. Montalvo, and J. Román. 2012. Fauna de Vertebrados del Ecuador. Escuela Politécnica Nacional. Quito, Ecuador.

Bank, F. G., C. L. Irwin, G. L. Evink, M. E. Gray, S. Hagood, J. R. Kinar, A. Levy, D. Paulson, B. Ruediger, R. M. Sauvajot, D. J. Scott, and P. White. 2002. Wildlife habitat connectivity across European highways. American Trade Initiatives. Alexandria, U. S. A.

Barthelmess, E. L. 2016. Family Erethizontidae. Pp. 372–397, in Handbook of Mammals of the World. Vol. 6. Lagomorphs and Rodents: Part 1 (Wilson, D. E., Lacher, T. E., and Mittermeier, R. A, eds.). Lynx, Barcelona, España.

Braunisch, V., K. Bollmann, R. F. Graf, and A. H. Hirzel. 2008. Living on the edge—modeling habitat suitability for species at the edge of their fundamental niche. Ecological Modelling 214:153–167.

Brito, J., and R. Ojala Barbour. 2016. Mamíferos no voladores del Parque Nacional Sangay, Ecuador. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia 56:45–61.

Brito, J., M. A. Camacho, V. Romero, and A. F. Vallejo. 2018. Mamíferos de Ecuador. Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Versión 2018.0. https://bioweb.bio/faunaweb/mammaliaweb/. Consultado el 23 de febrero 2018.

Cerón, C., W. Palacios, R. Valencia, and R. Sierra. 1999. Las formaciones naturales de la Costa del Ecuador. Propuesta preliminar de un sistema de clasificación de vegetación para el Ecuador continental. Proyecto INEFAN/GERF-BIRF y Ecociencia. Quito, Ecuador.

Chatterjee, H. J., J. S. Y. Tse, and S. T. Turvey. 2012. Using ecological niche modelling to predict spatial and temporal distribution patterns in Chinese gibbons: lessons from the present and the past. Folia Primatologica 83: 85–99.

Cuesta, F., M. Peralvo, A. Merino-Viteri, M. Bustamante, F. Baquero, J. F. Freile, and O. Torres-Carvajal. 2017. Priority areas for biodiversity conservation in mainland Ecuador. Neotropical Biodiversity 3:93–106.

Elith, J., C. H. Graham, R. P. Anderson, M. Dudı´k, S. Ferrier, Guisan, A., R. J. Hijmans, F. Huettmann, J. R. Leathwick, A. Lehmann, J. Li, L. G. Lohmann, B. A. Loiselle, G. Manion, C. Moritz, M. Nakamura, Nakazawa, J. McC. Overton, A. T. Peterson, S. J. Phillips, K. S. Richardson, R. Scachetti-Pereira, R. E. Schapire, J. Sobero´n, S. Williams, M. S. Wisz, and N. E. Zimmermann. 2006. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29:129–151.

Elith, J., S. J. Phillips, T. Hastie, M. Didík, Y. E. Chee, and C. J. Yates. 2011. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists. Diversity and Distributions 17:43–57.

Esri. 2017. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10 v.5.1 Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute.

Fernández de Córdoba-Torres, J., and C. Nivelo. 2016. Guía de mamíferos de las zonas urbana y periurbanas de Cuenca. Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado Municipal del Cantón Cuenca y Comisión Ambiental Universidad del Azuay. Cuenca, Ecuador.

Gray, J. E. 1865. Notice of an apparently undescribed species of American porcupine. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 33:321–322.

Grillo, C, J. A. Bissonette, and P. C. Cramer. 2010. Mitigation Measures to Reduce Impacts on Biodiversity. Pp. 73–114, in Highways: Construction, Management, and Maintenance. (Jones, S. R, ed). Frank Columbus, U. S. A.

Hanley, J. A., and B. J. McNeil. 1982. The meaning and use of the area under a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143:29–36.

Hijmans, R., S., Cameron, J. Parra P. G. Jones, and A. Jarvis. 2005. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 25:1965–1978.

Kerley, G. I. H., R. Kowalczyk, and J. P. G. M. Cromsigt. 2012. Conservation implications of the refugee species concept and the European bison: king of the forest or refugee in a marginal habitat? Ecography 35:519–529.

Lacépède, B. G. E. de la V. 1799. Tableau des divisions, sous-divivisions, orders et genres des Mammifères. Supplement to Discours d’ouverture et de clôture du cours d’histoire naturelle donné dans le Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, l’an VII de la République, et tableau méthodiques des mammifères et de oiseaux. Paris, France.

Liu, C., P. M. Berry, T. P. Dawson, and R. G. Pearson. 2005. Selecting thresholds of occurrence in the prediction of species distributions. Ecography 28:385–393.

Lizcaíno, D., D. Prieto-Torres, and M. Ortega-Andrade. 2015. Distribución de la danta de montaña (Tapirus pinchaque) en Colombia: importancia de las áreas no protegidas para la conservación en escenarios de cambio climático. Pp. 115–129, in Conservación de grandes vertebrados en áreas no protegidas de Colombia, Venezuela y Brasil (Payán, E., C. Lasso, and C. Castaño-Uribe, eds.). Serie Editorial Fauna Silvestre Neotropical. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humbolt (IAvH). Bogotá, Colombia.

Lobo, J. M., A. Jiménez-Valverde, and R. Real. 2008. AUC: a misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models. Global Ecology and Biogeography 17:145–151.

Lozano, P., R. W. Bussmann, and M. Küppers. 2006. Landslides as ecosystem disturbance-their implications and importance in Southern Ecuador. Lyonia 9:75–81.

Marmion, M., M. Parviainen, M. Luoto, R. K. Heikkinen, and W. Thuiller. 2009. Evaluation of consensus methods in predictive species distribution modelling. Diversity and distributions 15:59–69.

Menéndez-Guerrero, P., and C. Graham. 2013. Evaluating multiple causes of amphibian declines of Ecuador using geographical quantitative analyses. Ecography 36:001–014.

MINAM. 2017. Ministerio del Ambiente del Perú. http://www.minam.gob.pe/. Fecha de acceso 17 mayo 2017.

Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador. 2013. Sistema de clasificación de los ecosistemas del Ecuador continental. Subsecretaría de Patrimonio Natural. Quito, Ecuador.

Monge, C., and F. Leon-Velarde. 1991. Physiological adaptation to high altitude: oxygen transport in mammals and birds. Physiological Reviews 71:1135–1172.

More, A., and S. Crespo. 2016. Documented records of the stump-tailed porcupine Coendou rufescens (Erethizontidae, Rodentia) in northwestern Peru. The Biologist 14:359–369.

Morueta-Holme, N., C. Fløjgaard, and J. C. Svenning. 2010. Climate change risks and conservation implications for a threatened small-range mammal species. PloS One 5: e10360.

Muñoz-Ortiz, A., Á. A. Velásquez-Álvarez, C. E. Guarnizo, and A. J. Crawford. 2015. Of peaks and valleys: testing the roles of orogeny and habitat heterogeneity in driving allopatry in mid-elevation frogs (Aromobatidae: Rheobates) of the northern Andes. Journal of Biogeography 42:193–205.

Nüchel, J., P. K. Bøcher, W. Xiao, A. X. Zhu, and J. C. Svenning. 2018. Snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus): potential distribution and its implication for conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation 1–22.

Orcés, G., and L. Albuja. 2004. Presencia de Speothos venaticus (Carnivora: Canidae) en el Ecuador occidental y nuevo registro de Coendou rufescens (Rodentia: Erethizontidae) en el Ecuador. Politécnica 25, Biología 5:11–18.

Ortega-Andrade, H. M, D. A, Prieto-Torres, I. Gómez-Lora, and D. J. Lizcano. 2015. Ecological and Geographical Analysis of the Distribution of the Mountain Tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) en Ecuador: Importance of Protected Areas in Future Scenarios of Global Warming. PLoS ONE 10:e0121137.

Osorio-Olvera, L. 2018. Niche Toolbox. http://shiny.conabio.gob.mx:3838/nichetoolb2/. Consultado el 23 de noviembre 2017.

Peterson A.T, M. PapeÅŸ, and J. Soberón. 2008. Rethinking receiver operating characteristic analysis applications in ecological niche modeling. Ecological Modelling 213: 63–72.

Peterson, A. T, J. Soberón, R. G. Pearson, R. P. Anderson, E. Martínez-Meyer, M. Nakamura, and M. B. Aráujo. 2011. Ecological niches and geographic distributions (MPB-49). Princeton University Press.

Phillips, S. J, and M. Dudík. 2008. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluate on. Ecography 31:161–175.

Phillips, S, R. P. Anderson, and R, E. Schapire. 2006. Maximum entropy modelling of species geographic distributions. Ecological Modelling 190:231–259.

Qiao, H., J. Soberón, and A. T. Peterson. 2015. No silver bullets in correlative ecological niche modelling: insights from testing among many potential algorithms for niche estimation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 6:1126–1136.

R Core Team. 2016. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/.

Ramírez-Chaves, H. E., W. Pérez, and J. Ramírez-Mosquera. 2008. Mamíferos presentes en el municipio de Popayán, Cauca-Colombia. Boletín Científico Centro de Museos. Museo de Historia Natural 12:65–89.

Ramírez-Chaves, H. E., A. F. Suárez-Castro, D. M. Morales-Martínez, and M. C. Vallejo-Pareja. 2016. Richness and distribution of porcupines (Erethizontidae: Coendou) from Colombia. Mammalia 80:181–191.

Renner, I. W., and D. I. Warton. 2013. Equivalence of MAXENT and Poisson Point Process Models for Species Distribution Modeling in Ecology. Biometrics 69:274–281.

Reyes-Puig, C., C. Almendáriz, and O. Torres-Carvajal. 2017. Diversity, threat, and conservation of reptiles from continental Ecuador. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation 11:51–58.

Rodas, L. F., F. Sánchez, L. Cuenca, and J. Manzanilla. 2007. Manual de Procedimientos contra el Tráfico Ilegal de Fauna en el Ecuador. Naturaleza and Cultura Internacional, DarwinNet y Ministerio del Ambiente. Loja, Ecuador.

Romero, V., C. Racines-Márquez, and J. Brito. 2018. A short review and worldwide list of wild albino rodents with the first report of albinism in Coendou rufescens (Rodentia: Erethizontidae). Mammalia 82: DOI:10.1515/mammalia-2017-0111

Sánchez, F., B. Gómez-valencia, S. J. Álvarez, and M. Gómez-laverde. 2008. Primeros datos sobre los hábitos alimentarios del tigrillo, Leopardus pardalis, en un bosque andino de Colombia. Revista UDCA Actualidad y Divulgación Científica 11:101–107.

Siac. 2017. Sistema de Información ambiental de Colombia. www.siac.gov.co/. Consultado el 14 mayo 2017.

Sin. 2017. Sistema Nacional de Información. http://sni.gob.ec/. Consultado el 14 mayo 2017.

Tirira, D., and C. Boada. 2009. Diversidad de mamíferos en bosques de Ceja Andina alta del nororiente de la provincia de Carchi, Ecuador. Boletín Técnico 8, Ecuador Serie Zoológica 4–5:1–24.

Tirira, D. 2016. Coendou rufescens. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2016. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/7010/0. Consultado el 20 agosto 2017.

Tirira, D. 2017. Guía de campo de los mamíferos del Ecuador. Ediciones Murciélago Blanco. Quito, Ecuador.

Valencia, R., C. Cerón, and W. Palacios. 1999. Las formaciones naturales de la Sierra del Ecuador. Propuesta preliminar de un sistema de clasificación de vegetación para el ecuador continental. Proyecto INEFAN/GEF-BIRF y EcoCiencia. Quito, Ecuador.

Vallejo, A. F., and C. Boada. 2017. Coendou rufescens. In, Mamíferos de Ecuador. (Brito, J., M. A. Camacho, and V. Romero. eds). Versión 2017.0. Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador. https://www.bioweb.bio/faunaweb/mammaliaweb/FichaEspecie/Coendou%20rufescens. Consultado el 20 de agosto 2017.

Voss, R. S. 2011. Revisionary Notes on Neotropical Porcupines (Rodentia: Erethizontidae). An annotated Checklist of the species of Coendou Lacépède, 1799. American Museum Novitates 20:1–36.

Voss, R. S. 2015. Family Erethizontidae Bonaparte, 1845. Pp. 786–805, in Mammals of South America, Volume 2: Rodents. (Patton, J. L., U. F. J. Pardiñas, and G. D’Elía, eds.). The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, U. S. A.

Voss, R. S., C. Hubbard, and S. A. Jansa. 2013. Phylogenetic relationships of New World porcupines (Rodentia, Erethizontidae): implications for taxonomy, morphological evolution, and biogeography. American Museum Novitates 3769:1–36.

Williams, R. 2008. Mamíferos de Chaparrí. Pp. 78–85, in Guía de la vida silvestre de Chaparrí. (Plenge, H.,and R. Williams, eds.). Geográfica EIRL. Lima, Perú.

Zhu, G. P., and A. T. Peterson. 2017. Do consensus models outperform individual models? Transferability evaluations of diverse modeling approaches for an invasive moth. Biological Invasions 19:2519-2532.

Published

Issue

Section

License

THERYA is based on its open access policy allowing free download of the complete contents of the magazine in digital format. It also authorizes the author to place the article in the format published by the magazine on your personal website, or in an open access repository, distribute copies of the article published in electronic or printed format that the author deems appropriate, and reuse part or whole article in own articles or future books, giving the corresponding credits.